Pierre Deval was born in 1897 in Lyon, the youngest child of a family of silk manufacturers whose commercial networks spanned the globe. Self-taught from a young age, he set up his first studio near the family home and began by copying the Old Masters. The plaster cast museum became a key site in his early training.

Deeply influenced by Rodin, Deval was moved by the purity of the master’s lines, the expressive power of his drawings, and the sensuality of his figures. Music, literature, and poetry fed the budding painter’s imagination. He painted passionately, though with deliberate slowness.

Mobilized during World War I, Deval—who had suffered from lung problems since childhood—was soon sent home and spent the rest of the conflict in convalescence. In 1921, he moved to Paris to refine his training. After a brief period in the Cormon studio, he joined the Académie de la Grande Chaumière, studying under Émile-René Ménard and Lucien Simon.

Through his friend Jacques Rigaut, he met Tristan Tzara, a leading figure in the Dada movement. In the early 1920s, he co-founded the literary journal Promenoir with Jean Lacroix and Jean Epstein. Though short-lived—only six issues—the publication drew contributions from major avant-garde figures including Cendrars, Cocteau, Soupault, Léger, and Ozenfant. Firmly anchored in his native Lyon, Deval organized an exhibition there titled Cubism, Purism, Expressionism, introducing avant-garde painting to local audiences.

Despite his interest in modernity and the rapidity of his times, Deval chose a classical path. He retained traditional approaches to line and composition, aligning himself with the rappel à l’ordre movement, which after the war called for a return to the roots of pictorial tradition. He produced decorative panels and portraits that showed his debt to the masters of the past, while subtly embracing modernity.

His debut at the Salon, Ariane, won the Jean-Julien Lemordant Prize. Art critic Léonce Bénédite wanted to acquire it for the Musée du Luxembourg. The painting also earned Deval a residency grant at the Villa Abd-el-Tif. In the autumn of 1922, he set off for a two-year stay in Algeria.

There, he joined fellow laureates Jean Bouchaud and Maurice Bouviolle, sharing the villa—often likened to an Orientalist Villa Medici—with sculptor Ludovic Pineau. He traveled extensively through southern Algeria and visited Morocco. In time, Deval distanced himself from the colonial spirit of the Abd-el-Tif tradition, embodied by Bénédite. He often declined to take part in official exhibitions, and his work diverged from the expected style of the villa’s residents. His 1924 painting La Plage caused a stir in Algiers due to its frankness—though not provocative by Parisian standards, it introduced a new form of modernity to the local scene.

In Algeria, Deval met Albert Marquet, 22 years his senior, and a lasting friendship was born. Deval had married his fiancée Henriette, who had accompanied him to Algeria. Back in Paris, the couple settled on quai Saint-Michel in the same building as Marquet and Jacqueline Marval, an apartment once occupied by Matisse.

The Marquets and Devals became inseparable. In 1925, Marquet invited them to Norway, where a collector had lent him a large house. Other shared stays followed in Marseille and Porquerolles. At Marquet’s side, Deval met several former Fauves, including Camoin, Manguin, Jean Puy, and Matisse.

In the spring of 1925, the Devals discovered the Domaine d’Orvès, an 18th-century estate near La Valette-du-Var, then nearly abandoned. They fell in love with the place and settled there immediately. The novelist Henri Bosco was among the enchanted visitors, drawn to the unique atmosphere of the historic home and its lush garden, fed by natural springs and dotted with fishponds and pines.

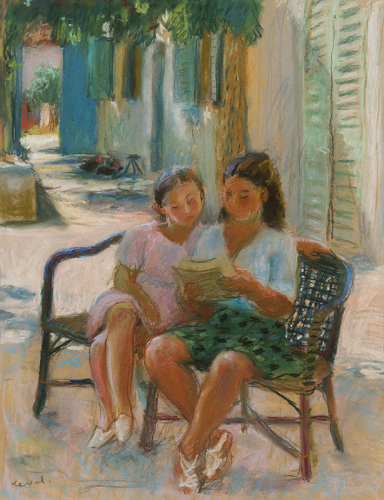

In 1927, Deval accompanied Bosco to Greece in pursuit of the classical myths that fascinated them both. Though now living in the Var, Deval remained active in the Lyon and Paris art scenes. He exhibited at official Salons and in galleries such as Carmine (1927) and Druet (1929). Much of his work centered on the female figure. Models came and went at Orvès, each inspiring an atmosphere of sensuality shaped by her archetype.

His friend, collector and critic Georges Besson, kept him informed of the Parisian art world. In 1930, Deval’s brother Jean, who had overseen the family silk business, died. The company collapsed, leaving Deval to manage without the financial safety net it had provided. He worked tirelessly, helped by Besson, to establish gallery contacts and relied on portrait commissions—works he considered merely "bread-and-butter"—to support his family and maintain Orvès.

The writer Pierre-Jean Jouve and his wife, one of France’s first psychoanalysts, stayed a summer at Orvès, introduced by mutual friends Willy Eisenschitz and Claire Bertrand. The domain cast its spell on many visiting artists and creators.

Life went on, far from Paris, with Deval and Henriette raising their two children, Philippe and Françoise. During the Occupation, German officers were quartered at Orvès. In 1944, the Devals were evicted and relocated to a nearby farm, then to the foot of Mont Ventoux. The estate suffered terribly—over a thousand trees were felled.

After the Liberation, they returned and began the long restoration of the house and gardens. In 1951, a falling-out with Georges Besson ended their friendship and cut Deval off from his influential ally in the Parisian art world.

Nonetheless, Deval resumed exhibiting in Toulon, Lyon, Geneva, Mulhouse, and Aix-en-Provence. In 1971, the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Toulon held a retrospective of his work. Nearing one hundred years of age, Pierre Deval died in the shade of the olive trees at Orvès, the place that had defined his life and art.

Deval in His Domain

8 May 2025 - 11 May 2025

Salon du Dessin

26 March 2025 - 31 March 2025